Meanwhile, elsewhere:

The restoration of Rogue (1892)

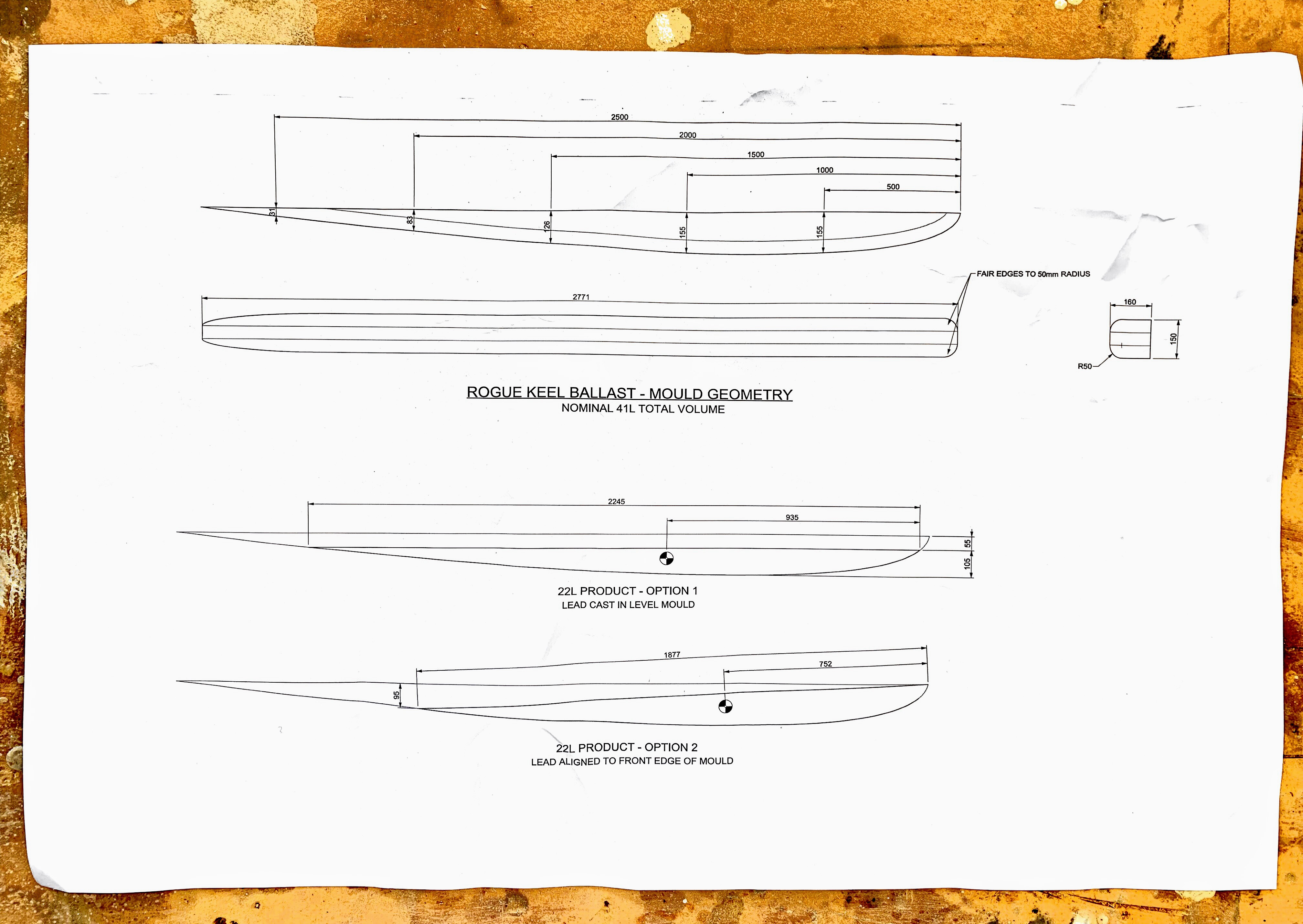

Rogue is a triple-skin kauri hulled, flush decked, gaff rigged 32' racing cutter from NZ — Chas Bailey Jr's first design.

Meanwhile, elsewhere:

Plans for a pre-Xmas splash are stymied by collapse of uncertified crane in closest marina, about which I’d not been sanguine in any event. So, mid-January instead. Meantime …

Sean Garwood, a Nelson-based artist, presently has a New Zealand maritime-themed exhibition — “A Painted Voyage” — at Parnell’s Jonathan Grant Gallery. It includes a representation of the Bailey Boatyard at Auckland’s Freemans Bay …

… and of Charles Bailey Sr’s 1893 masterpiece, Viking, coming around the Waitemata Harbour’s North Head in a staunch north-westerly, leaving Rangitoto behind. On the bow of the Logan launch, Doreen, is depicted marine photographer, Henry Winkelmann.

The actual photograph may be this (sailorly decorum dousing extras):

And the Auckland Star’s 23 December 1893 account of Viking’s build:

She is a very handsome looking little vessel lying in the water, and unless appearances are very deceptive will make an excellent sea boat. There is a pretty schooner bow, and a long overhanging counter and gold scroll work and encircling bands, admirably relieve the white painted sides. So far as details are concerned, the timber used was kauri, with pohutakawa knees and floors, and an iron bark stem and rudder post. She is diagonally built of three thicknesses, and is copper fastened throughout and coppered. She is 46 feet on the water line, 67 feet over all, 12 foot beam, and draws about 9 feet of water. The deck fittings are of teak, and below some beautifully mottled kauri has been used as panels with rimu and kahikatea. There is a forecastle fitted up with a host of most ingenious contrivances, saloon with lockers, drawers, a wine press, a library, and folding berths equal to accommodating 8 persons comfortably. The cushions are of crimson velvet, and the ceiling is painted white and relieved with gold. There is a ladies’ cabin aft with two berths and innumerable drawers, besides which a lavatory and all other conveniences have not been neglected. The yacht is fitted with a mast 34 feet from deck to hounds, or 50 feet full length, and a topmast 26 feet. The boom is 45 feet long, and the gaff 30 feet. The bowsprit projects 16 feet from the stern. For ordinary cruising, the Viking will be rigged as a yawl, and for racing as a cutter. Naturally she will have an immense spread of canvas. The spars are of Oregon pine, and only brass and galvanised iron materials have been used. A neat windlass forward will be found very handy, and altogether it will be difficult to find a superior to the Viking among the sailing crafts this side of the Line.

On the way to that, I came across the New Zealand Geographic’s fabulously illustrated Jan 2000 “Grace Under Sail”. It’s worth a read.